2 Paintings in Collection

Mainie Jellett

JELLETT, MAINIE

(1897 - 1944) Ireland

Works in Public Collections

The National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland; Crawford Art Gallery, Cork, Ireland; Niland Art Collection, Sligo, Ireland; Butler Gallery, Kilkenny, Ireland; Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland; The Huge Lane Municipal Gallery, Dublin, Ireland; Ulster Museum, Belfast, UK; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland

Recent Exhibitions

Analysing Cubism, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland, 2013

Women Artists in the Modernist Tradition, Boise Art Museum, ID, 2002

Abstract and Nude Included

Uncovered and Recovered: Women Artists in the Modernist Tradition, Sun Valley Museum of Art, Ketchum, ID, 1999

Abstract and Nude Included

Publications

Mainie Jellett and the Modern Movement in Ireland, by Bruce Arnold, Yale University Press, 1992

Mainie Jellett 1897-1944, Irish Museum of Modern Art, 1991

Mainie Jellett: The Artist’s Vision by Mainie Jellett with introduction by Albert Gleizes, Dundalgan Pres, Dundalk, 1958

Other Resources

In 1990 Bruce Arnold produced, scripted, and narrated a documentary To Make it Live-Mainie Jellett

Born 1897 Dublin, Ireland

Died 1944 Dublin, Ireland

Mainie Jellett was the pioneer of Modernism in Ireland. As a young artist, she and her life-long friend Evie Hone studied in Paris, absorbing a cubist approach to painting. When Jellett returned to Ireland she spent the remainder of her life promoting and defining modernism for the Irish public. She was heard from frequently via published articles, radio interviews, public meetings, and exhibitions.

Born into a wealthy Protestant family, Jellett took classes in drawing, painting and piano in Dublin and then went on to Westminster School in London where she studied with Walter Sickert, a painter who knew the work of the French Impressionists. She met Evie Hone at Westminster and Sickert encouraged them to visit André Lhote, a cubist painter and teacher who lived in Paris. The two took classes from Lhote and, working from live models, adopted Lhote's approach of using the lines suggested by the figure as the pattern for constructing a composition. This kind of academic cubism proposed reducing form to simple shapes and then integrating those into a geometric pattern.

After working with Lhote for a year, Jellett felt the need to stretch beyond his thinking and sought out painter Alfred Gleizes who taught a more abstract approach to cubism. She and Hone worked with Gleizes for a number of months every year from 1922 until 1931. Clearly inspired to be working in a completely abstract manner, Jellett absorbed Gleizes' philosophy and his ideas of "translation and rotation,” where the painting moves around a central axis. Jellett’s early work from this period involved a single compositional element; later she used two or four elements.

In addition to his structural approach, Gleizes’ theories about color and its symbolism appealed to Jellett who believed that color and form had a universal language that transcended culture or language barriers. While Gleizes had a system where certain colors were used in relation to each other, Jellett used color more intuitively. In Irish Art, a Concise History Bruce Arnold observes: Many of her abstracts are built up from a central 'eye' or 'heart' in arcs of colour, held up and together by the rhythm of line and shape, and given depth and intensity - a sense of abstract perspective - by the basic understanding of light and colour. Jellett worked through a process where she made detailed studies of her subject and then searched for what she considered the rhythms and movements of the form. She transposed these elements in a systematic manner with the goal of creating a new harmonious work. While her art reflects the influences of both Gleizes and Lhote, ultimately it remains specifically hers.

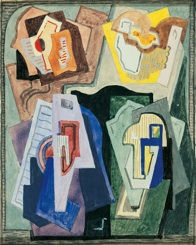

A committed Christian, Jellett often used religious iconography for her subject matter. The single vertical figure in Nude could be read as a Madonna figure. Jellett also had a keen interest in Renaissance painting, which she often reinterpreted in a cubist fashion. In Nude one can clearly determine the figurative core of the work that she then built on, moving outward to the decorative framed edges. The lines and dots that compose the frame of the figure are frequently used elements that break up the geometry of shapes. Abstract is divided into four components involving shapes that shift and rotate, exemplifying the structural methodology that she learned from Gleizes. Made up of a multiplicity of interlocked forms, each of the four sections are defined by a harmonious color grouping. She employs contrasting colors and decorative patterning to distinguish each area from the others. The layered greens and grays of the background provide a cohesive element.

In 1923 Jellett introduced her modernist approach, exhibiting two of her cubist painting at the Dublin Painters' Exhibition. The response was nothing short of hostile. The Irish Times published a photograph of Decoration and included their critic’s commentary: they are all squares, cubes, odd shapes and clashing colours. They may, to the man who understands the most up-to-date modern art, mean something; but to me they presented an insoluble puzzle. A fellow painter and critic, George Russell, referred to her work in the Irish Statesman as the ‘sub-human art of Miss Jellett.’

The negative audience response did not dissuade Jellett and a year later she and Hone had their first and only joint exhibition at the Dublin Painters’ Gallery. While she was fighting a battle against conservatism at home, exhibitions of Jellett's painting in London and Paris between 1923 & 1926 won her high praise. She exhibited at the Salon des Indépendents 1923, 1924 & 1925. The 1925 exhibition was L’Art d’Aujourd ‘hui, a major modernist exhibition attracting international attention where she exhibited alongside Gleizes, Delaunay and Leger. Recognized as a leader and articulate voice for abstraction, she took part in the first publication of Abstraction-Création, one of the foundational organizations of European abstraction in the early 1930s which included Jean Arp, Alexander Calder, Gleizes, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Mondrian and Kurt Schwitters.

Jellett could have easily lived in Paris and had a successful career yet she chose to be in Ireland where the art world remained suspicious of abstraction. Realistic landscapes and portraiture were the acceptable approach. In fact the Roman Catholic Church was so leery of modernism that they would censor work that was outside the prescribed norm. But Jellett was excited by modernism’s promise and throughout the 1920s and early 1930s she continued to share her paintings, exhibiting annually at the Dublin Painters Gallery 1926-1929.

In February of 1926 Jellett gave her first public lecture on “Cubism and Subsequent Movements in Painting” at the Dublin Literary Society. Stating “when imitation is the chief aim of art the creative power dies.” She also defended the primary foundational idea behind cubism that painting had to respond to the two dimensional flatness of the picture plane and that non-representational art was a direct result of that commitment.

By the 1930s, Jellett’s abstraction had given way to a hybrid style, which united cubism, religious art and Celtic design, creating paintings that were both recognizably Irish and modern. Figurative elements reappeared and her later body of work includes landscapes. From 1930-1937, she showed at the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA). She also exhibited with the Water Colour Society of Ireland between 1931 and 1943. But these established institutions were not fulfilling the need for modernism to be seen and shared in Ireland so Jellett helped to found the Irish Exhibition of Living Art and became its first chairperson in 1943. This exhibiting society became the main venue for avant-garde art in Ireland for many years and helped the Irish public understand modernism.

It wasn't until the mid-1930s that Irish critics began to recognize Jellett for her important, progressive work. In 1939 her paintings represented Ireland at the New York World’s Fair. Biographer Bruce Arnold notes Jellett’s lifelong advocacy and leadership as a modernist stating that she was the only painter who consistently produced and exhibited pure abstract works during the 1920s in the British Isles. By the time of her death in 1944, Mainie Jellett was celebrated as the grande dame of Irish modernism and today her art is included in the collections of major museums in Ireland.